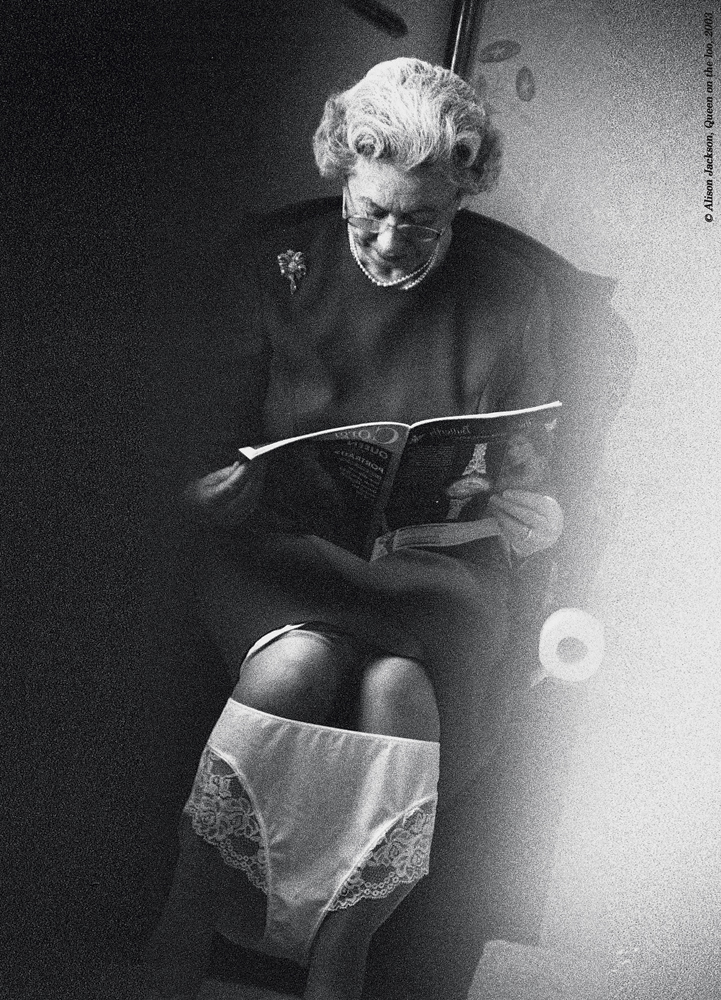

It jars our sense of reality to see the Queen having a good read on the toilet, her panties pulled down below her knees; Yet the ‘suspected’ imaginary realm containing these and many other examples of celebrity photography is far from imaginary. In fact, it’s excruciatingly real judging on the basis of everything that goes into making it seem real. Alison Jackson’s photography creates a world of simulations. Her jaw-dropping images hurl mental darts at celebrities and capture their everydayness, neuroses, and simplest of bodily needs. At the same, however, her images turn celebrities into the carriers and perpetrators of a false reality.

Jackson’s photographic artistry is crowned by the fact that she creates every aspect of these images herself, and achieves staggering creative results without resorting to special effects or alterations. Despite their appearing real or authentic, the compromised celebrities depicted in her photographs are never the real McCoy but rather ‘spitting images’ or lookalikes found through agencies around the world, and the voyeuristic situations that Jackson implants them in – settings which seem hijacked from reality by paparazzi cameras – serve as carefully contrived backdrops for ‘photographed performances’.

This is photography which does more than copy a staged-alias-false reality, this is bound up in our inherent greedy voyeurism, and in our need to create a folk religion.

A graduate of the Royal College of Art in London, Jackson’s work first caught the attention of a large audience with her 1999 visual simulation of Princess Diana and Dodi Fayed with their supposed mixed-race child. Since then the recipient of a BAFTA and several other awards, Jackson continues to astonish viewers in Europe and abroad with her creations.

Karl Johnson: While you were at the Royal College of Art in London, what made you change from studying sculpture to studying photography?

Alison Jackson: Well, I made performances then. They were live performances which involved real people. Soon I realized that there was a greater interest in seeing my photographs of these performances. Basically nothing was left after the performances were over. Only the photographs, which documented what had already happened. In the performances, different people did different things, but I obviously couldn’t freeze them in place. So I had to photograph them. And I came to concentrate on photography.

K.J.: How did that lead up to making celebrity photography?

A.J.: That was something which evolved from the work I was doing. I was studying the importance of the image: how important the image is over, say, the

real thing, and how we live our lives in a virtual world. Also, I was studying religious iconography and the fact that we only know the story of Christ through images. Of course, the crucifix is the biggest icon of all time! So I focused on trying to change people’s preconceptions about it. I experimented with the crucifix by attaching different things to it. I put, for example, a woman on the cross and tried lots of other subject matter, always using photography. Later, in performances, I would work with real things: a real woman, a real cross, and so on. Then I tried to see and make visible what the differences were. Interestingly enough, the viewers preferred to look at the photographs over the performance. An object is a lot easier to deal with, isn’t it?

K.J.: That description makes me think of Gilbert & George for some reason.

A.J.: Yes. I was fascinated by the work of Gilbert & George. In their performances they remained perfectly still and fixed in time as if standing in photographs.

With me, what mattered most was making photographs look more like live performances, making live performances look more like photographs, and then

to study the difference. I did that with a version of The Last Supper. I placed an installation of The Last Supper with real people at one end of a space, and a photograph of The Last Supper at the other. And while I tried to make the photograph look like the real thing, I tried to make the real thing look like the

photograph. I don’t know how successful that was. But it’s always interesting to see how viewers become seduced by photography.

Around that time, Princess Diana died and England came to a bit of a standstill. It wasn’t long before I saw this amazing phenomenon: nobody really knew Princess Diana except through the media photography which created her in their minds. Then I thought: If I use a lookalike of Princess Diana in a photograph, will people really know or even care that it’s not her? And I exhibited an image in the public mind, a family shot of Diana and Dodi and their mixed-race child. This quickly led to sensational speculations connected to her relationship with Dodi, and to her being, perhaps, murdered because of her pregnancy and the child. It was an iconic photograph, the sort of photo- graph that could have been taken by Snowdon. A Christ-like figure is in the center, and the strong, triangular composition of the picture makes it a very tradition work of photography, which displays the classic Madonna and child situation. Which this is not! It’s Diana and Dodi with their mixed-race baby.

All the expected references to Diana being sacred and idolized were there, though, everything an invention of the press and media. That fascinated me. How we all bought something invented by media imagery and materials. I was still at the Royal College of Art when I showed the Princess Diana photograph. But it was so scandalizing, so socially traumatizing, that I grew frightened. I felt as if I had to make other photographs right away in order to somehow disguise this one. That was when I began to make photographs about the Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky Affair, about the Royal Family, and about other well-known personalities in England. As my body of work grew, I began to make images of American and global celebrities.

K.J.: Would you say that today’s media puts more stock in presentation than it does in the truth, and that this, too, makes photography like yours so powerful – since most viewers don’t really want the truth as much as they do the presentation of ‘any’ truth?

A.J.: Perhaps. But in the case of the media, the truth is only a partial truth, isn’t it? The political arena makes it easy for politicians to lie on TV. They come in with a prepared script, say their bit, and then remove themselves without being scrutinized. All politicians are semi-actors!

K.J.: We know how most celebrities are ‘made’ to look. But, visually speaking, what are you trying to reach in your images of celebrities? How should the

image look?

A.J.: Even if it doesn’t seem obvious at first glance, I’m interested in the construction of iconic photography. Also, I respect classical imagery and the so-called three-quarter-view approach. The great portrait photography, for example, like Testino’s Princess Diana, and the classic images of Marilyn Monroe and Che Guevara. These are all very famous portraits, and all made in a similar way: always shot from below the head and nearly full on, showing a three quarter view, and always elongating the figures noses, depicting them in that Romanesque or Greek sculpture sort of way. Also, in each case, you see a brilliance behind the figure, and this leads your eye beyond the threequarter portrait and into the background. For me, this is an aspect of iconic photography. An exception might be Cecil Beaton, who often had a window nearby or behind the subject. I also think that, geometrically speaking, the construction of an iconic photograph clearly duplicates the geometry of a crucifix. Whether you’re religious or not, there is something beguiling about the image of Christ on the cross, and about the shape that it creates. When I study a face and register the horizontal bar of the eyes being intersected by the verticality of the nose right down to the neck, I imagine a geometric shape. Whether we notice it not, the picture’s composition is what lodges it in the mind and memory. Even tabloid

culture knows about all this. It understands the value of a good composition, and it uses it, too. That’s how you get this type of iconic photography in even cheap

magazines. It has a real purpose: to make celebrities desirable. So you have unexpected ‘compositional’ sophistication on the one hand, and a low perspective on the other.

K.J.: Are you ever disturbed by the godlike status that viewers give celebrities when they idolize them in photographs?

A.J.: Not at all. These images are beguiling for viewers! Which is precisely what I study in my work: the seductiveness of photography, the very nature of photography. For me, that includes the media and TV. It’s all very beguiling. Some people switch on the TV to get to sleep, because you don’t have to think; and we all know that TV cocoons you in a false sense of security. Other people leave their TV running for their cats and dogs. The images do it! Or look at the

celebrity and fashion magazine business. There are no words at all. It’s just picture after picture, and that makes people happy. We look at pictures all the time. The more we see certain celebrities, the more attractive and desirable they

become for us. Constantly seeing them turns them into saints, actually. You end up having saints of sex, saints of money, saints of ambition and so on. Each

celebrity comes to represent something in particular. Having so many saints spread around suits our culture rather well, I think. It’s certainly a lot better than having just ‘one’ Jesus. Not that the English go to church, mind you! That’s what all the celebrity magazines and tabloids are for. With celebrity magazines they practice their ‘folk religion’. Still, we live in a culture where real celebrities may or may not even exist. The celebrity is born of images, and the celebrity only

exists in images. You never really reach the celebrity. Wherever it involves this ‘folk religion’ of craving the celebrity, it’s always the same thing: What you can’t

get, you want more of. Basically, I think that it doesn’t make a bit of difference

whether the image is of the real celebrity or not. I don’t really think most people care. Just the same, the phenomenon is really uncanny. I invited my Princess Diana lookalike along to a friend’s gettogether for a drink one evening, and one of the other guests just stood in front of her perfectly tongue-tied and star-struck, unable to speak or behave properly. When I was in Madrid, there was a

similar incident. A crowd of people gathered around the David Beckham lookalike. Many of them were trying to kiss him, and they just wouldn’t take no for an answer until I showed them his passport. I had to prove to them, on paper, that he wasn’t the ‘real’ David Beckham.

K.J.: How long does it take you to find the perfect lookalike and then plan and produce a photograph?

A.J.: That depends. But it’s time consuming. It involves an enormous amount of work, and sometimes the photograph just can’t be made at all. I’m constantly looking for the right people, constantly chasing after possible lookalikes, constantly going up to perfect strangers on buses, in restaurants, and on planes – and constantly being rebuffed, tool! For locating lookalikes I work with casting agencies all over the world. In addition, I have an amazingly gifted casting director. Wigs are created for our actors. We make several light tests. It’s not just about lookalike photography. I’m not terribly interested in the lookalikes or celebrities. The real work is to construct a completely false reality.

K.J.: Do you think the obsession with celebrities and celebrity culture is more intense in the United States than it is in Europe?

A.J.: I don’t know for sure if the difference is so big.

What I think, though, is that things have changed in the States. Celebrities are, of course, extremely important. Even today Marilyn Monroe has the status

of a goddess. The difference is that over the last six years the States have discovered the tabloid culture that Britain always had. So now you have hundreds of new magazines. What’s interesting is that now the market embraces the fad of anti-celebrities. It zeroes in on a different angle. Suddenly you see, for

instance, Angelina Jolie on the front pages of newspapers looking old and wrinkled, and you read a lot of speculative reports on the lives of celebrities.

TEXT BY KARL E. JOHNSON

© picture: Alison Jackson

Well-known individuals depicted in this article are not “real”.

The photographs have been created using look-alikes.

The well-known individuals have not had any involvement in the

creation of the photographs and they have not approved them, nor has

their approval been sought for the publication of these photographs.

Image caption:

© Alison Jackson, Queen on the loo, 2003