What can a gorgeously crisp photo of a solitary Dutch Cape home in the Limpopo convey about South Africa’s apartheid? What does a sharp image of shadow and light on Coetzee Street in Middelburg, Eastern Cape, reveal about South Africa’s race relations? Or a gorgeous rugged canyon in the Richtersveld? A simple garden and home in Boksburg? Within these images – sparkling, clear and defined – lies the complex history of South Africa’s apartheid through the eyes of David Goldblatt, the country’s eminent documentary photographer. Goldblatt’s images are not of apartheid’s street clashes and broken bodies or any of the more dramatic subjects of documentary photography. Rather than capture the moments of conflict, Goldblatt’s images ask us to look deeper to their cause.

But to get his work for what it is – a detailed study and a kind of love letter to the country where he has lived for almost 80 years – you have to look beyond the physical beauty of his images. These are not just photos of churches and landscapes and people; contained within the stillness of the structures and monuments and places are the complex stories of people and a country struggling to find their place. Goldblatt works like a photographic anthropologist, and his life-long oeuvre serves as a multi-layered ethnography of South Africa: the land, the architecture, the Afrikaans landowners, black nomadic farmers, wealthy suburbanites, black migrant workers… His vision of South African is dynamic and comprehensive.

This means that for those of us who do not know South Africa like Goldblatt does, and there are few who do, the words that accompany Goldblatt’s images are important. In Intersections Intersected, the extensive text and captions that accompany each photo are required to get the full meaning of the image. For example, what might seem like a melancholy swath of dry farmland, if you look closer, is actually a landscape dotted in 1500 lavatories built in anticipation of the forced removal of a Mgwali farming community. Each landscape and that which is built on it carries a deliberate message for Goldblatt (as he once said in an interview, “Primary is the land, its division, possession, use, misuse. How we have shaped it and how it has shaped us.”) The photos, to have their full impact, require further inquiry.

One of the unexpected pleasures of getting to know Goldblatt’s work is exposure to the geography of South Africa. Each of his photos has a place name in the title. Terms unfamiliar to most non-South Africans hint at the diverse cultural history of the land. With names like the Transvaal, the Karoo, the Ciskei Bantustan, the Qwa Qwa and the Phuthaditjhaba, the titles of Goldblatt’s photos make you want to lay out a map of South Africa and trace out Goldblatt’s photographic journey over the years.

In terms of identity, Goldblatt is himself a kind of intersection. The son of Jewish Lithuanian parents who fled to South Africa to escape religious oppression, Goldblatt plays an unusual role in his country. His Jewish ancestry placed him in the religious minority, yet he himself claims to be uncertain about faith. He was also a white man in a racially segregated society. Not a part of the white Christian leadership and not a part of the black majority, Goldblatt is a South African outsider, yet one who is devoted to his country – so much so that he did not leave when the violence became extreme in the 1980s, a time when many white non-supporters of apartheid chose to leave.

In many ways, Goldblatt’s development as a photographer is inseparable from the politics that were taking over the country when he was a teenager. In 1948, when he was a senior in high school, he first became obsessed with photography. This was the same year that the National Party won the parliamentary elections and South Africa suddenly found itself under the leadership of white supremacists who believed they were predestined to rule the country. The mood change in South Africa was overwhelming; Goldblatt and his family and friends were thrust into a political climate of fear and foreboding. And Goldblatt decided to document the changes taking over his country.

At first his journey into photography was marred by setbacks. He attempted to photograph the political events happening around him, but found that he lacked both the composure and desire to be at the heart of the action and work under tense and violent circumstances. Even though the action-based documentary photography was the preferred style of the time, Goldblatt trusted his gut – he recognised that was not the type of photographer he wanted to be.

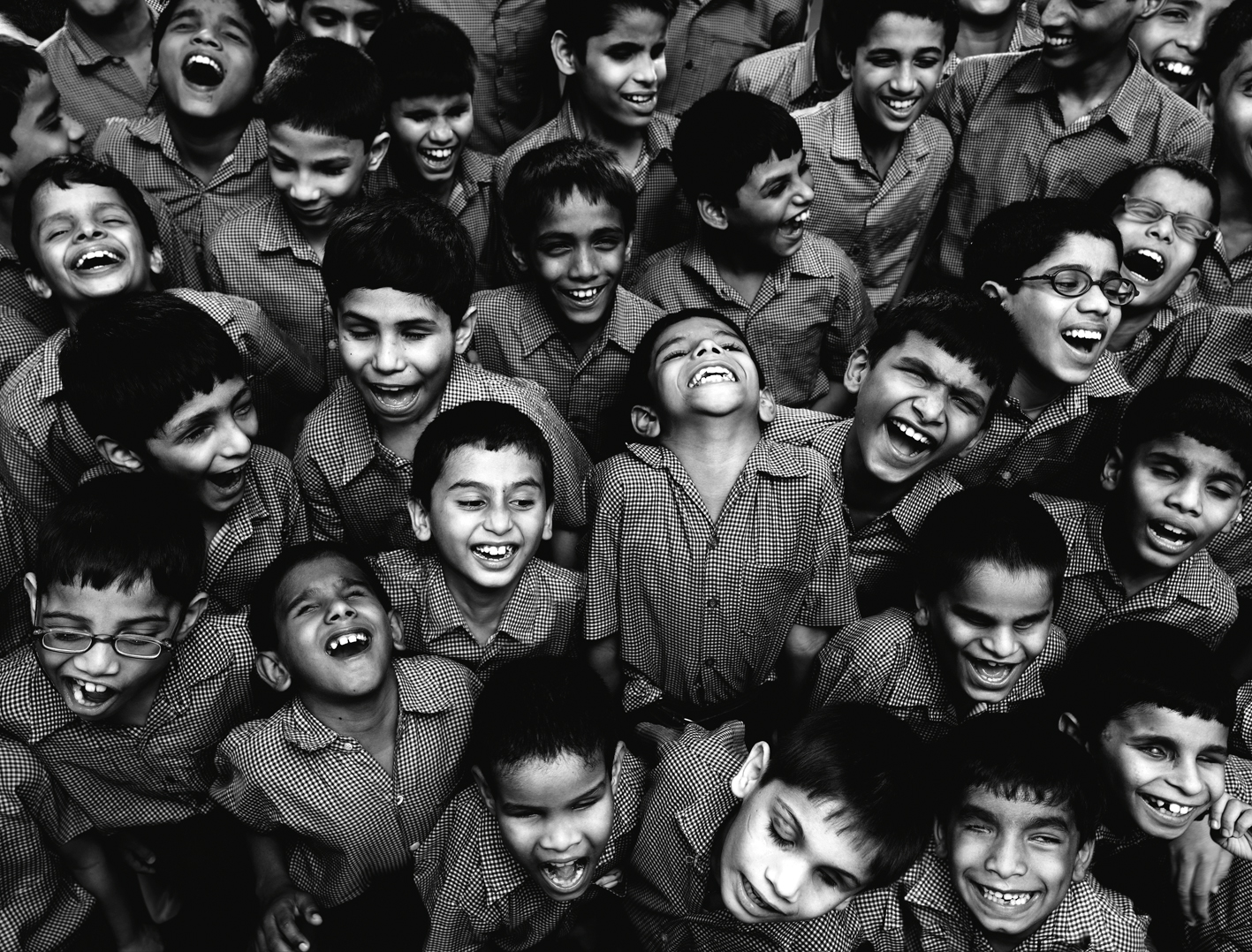

Uncertain about his future, Goldblatt retreated into university studies, family photographs and studying the craft of photography. In the 1960s, as apartheid intensified, Goldblatt found himself called to recording the quotidian realities of ordinary people and places. He writes, “…I had begun to realise an involvement with this place and the people among whom I lived that would not be stilled and that I needed to grasp and probe. I wanted to explore the specifics of our lives, not in theories but in the grit and taste and touch of things, and then bring those specifics into that particular and peculiar coherence that the camera both enables and demands.”

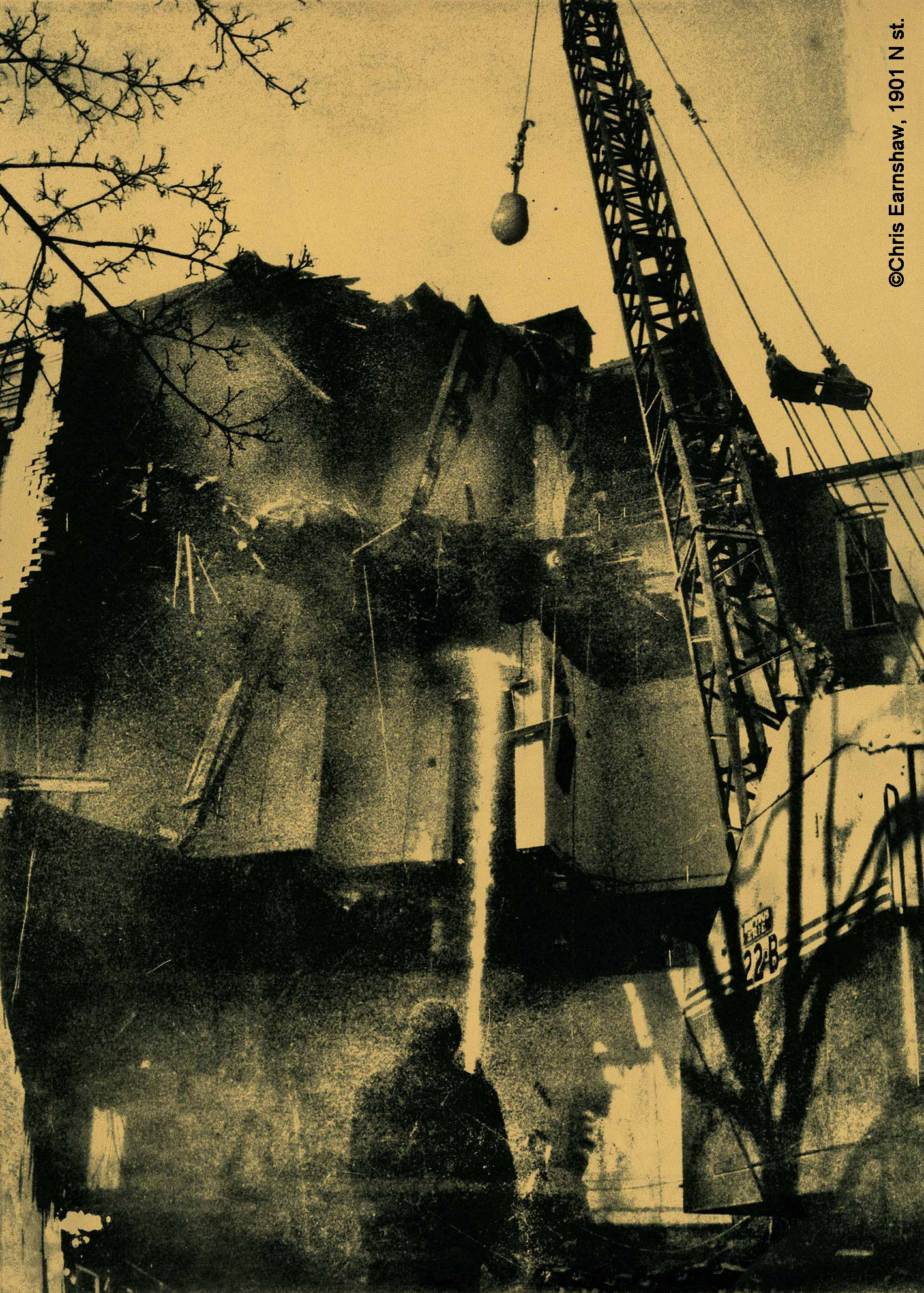

So Goldblatt avoided the police batons and protests of apartheid and threw himself into documenting the day-to-day existence of the people who lived through it. He felt particularly drawn to the structures of apartheid – its building and monuments and remains of resettlement plans. He writes, “It was to the quiet and commonplace where nothing ‘happened’ and yet all was contained and immanent that I was most drawn.”

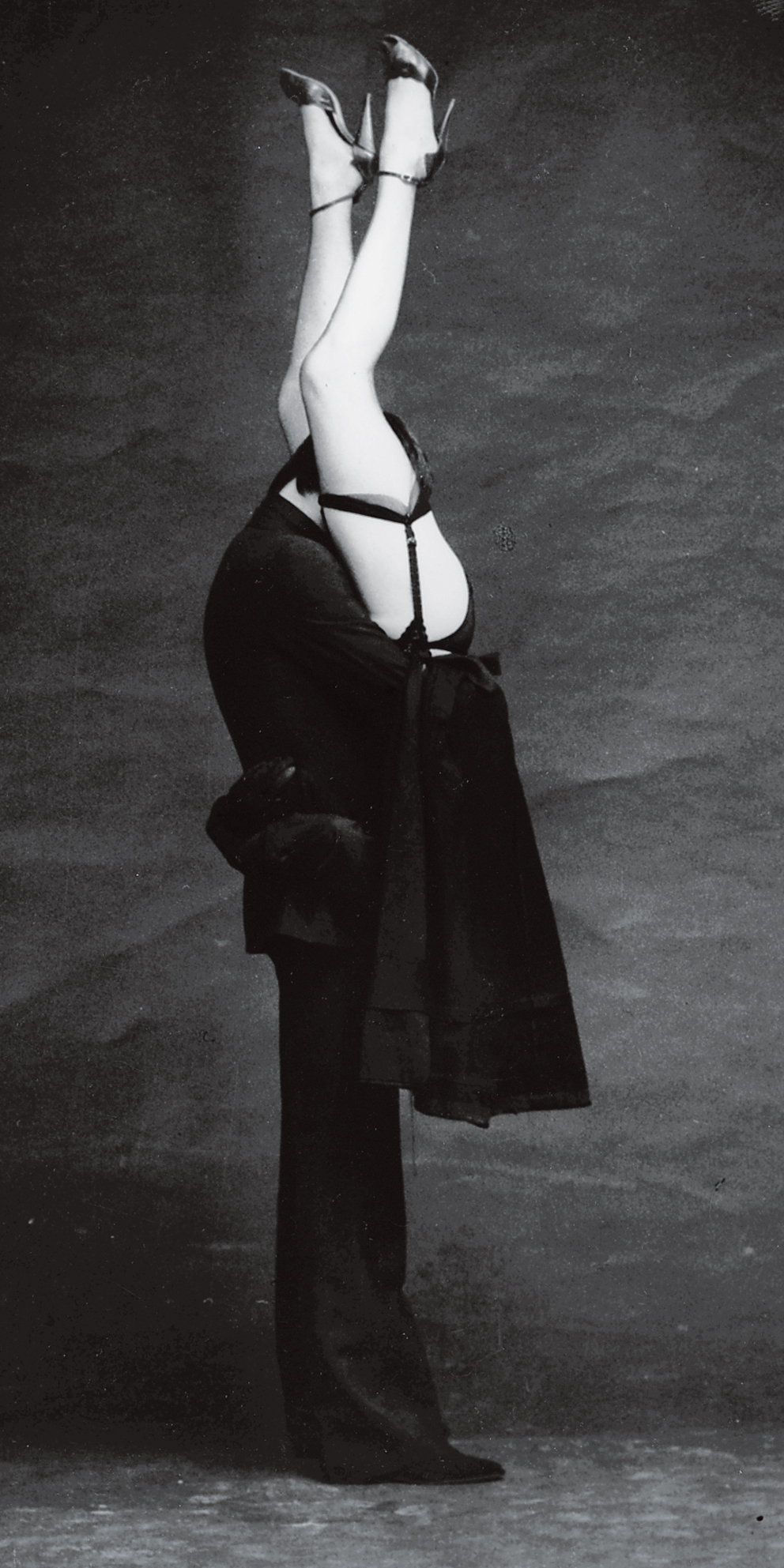

A key step in Goldblatt’s evolution as a vernacular photographer was learning to use the South African light. “…I had often been troubled by an unease with the tonal qualities of my photographs. They were quite lacking in the subtle gradations of work that I saw reproduced in magazines and books from Europe and the United States. Now I began to realise that in trying to emulate those qualities I had been false to our light. In much of South Africa the light is hard-edged and intense and integral to my sense of place. It is difficult to convey the excitement of this simple perception. Instead of fighting the light I began to embrace and work gladly within it. Congruence became possible between my awareness of what I knew so intimately and the photographs I attempted of it.” The power of stark shadow and light is what makes Goldblatt’s aesthetic so distinctly South African.

For a non-Christian with uncertain religious beliefs, Goldblatt has been particularly intrigued by churches, the ultimate physical expression of people’s faith. He became an expert in the architecture of the Afrikaner Protestant churches, whose leaders were often apartheid advocates. These churches seemed to embody the complexity and blindness of the times. Many of the active church members genuinely believed in the justness of apartheid and felt that their plan was good for whites and blacks alike. The architecture of the churches built during the apartheid, bold and towering in Goldblatt’s photographs, physically expressed this belief in their entitlement to rule the country. These structures and the hundreds of others that Goldblatt photographed tell us much about South Africa. As Goldblatt wrote, “The photographs…are about structures in South Africa which gave expression to or were evidence of some of the forces that shaped our society before the end of apartheid…our structures often declare quite nakedly, yet eloquently, what manner of people built them, and what they stood for.”

Goldblatt’s images make a strong argument why documentary photography should encompass more than the decisive, dramatic moment. By being subtler, Goldblatt permits a more nuanced, complex reading of the situation. When there is a photo with an overt story, of a white police officer beating a black man, for example, the immediate message is spelled out. But Goldblatt’s photos more readily speak to the complexity and background of a situation, something that is not always easily reduced to clear villains or heroes. Goldblatt’s subtlety allows a fuller reading of South Africa’s history, and perhaps brings us closer to a true understanding.

Text by Clayton Maxwell

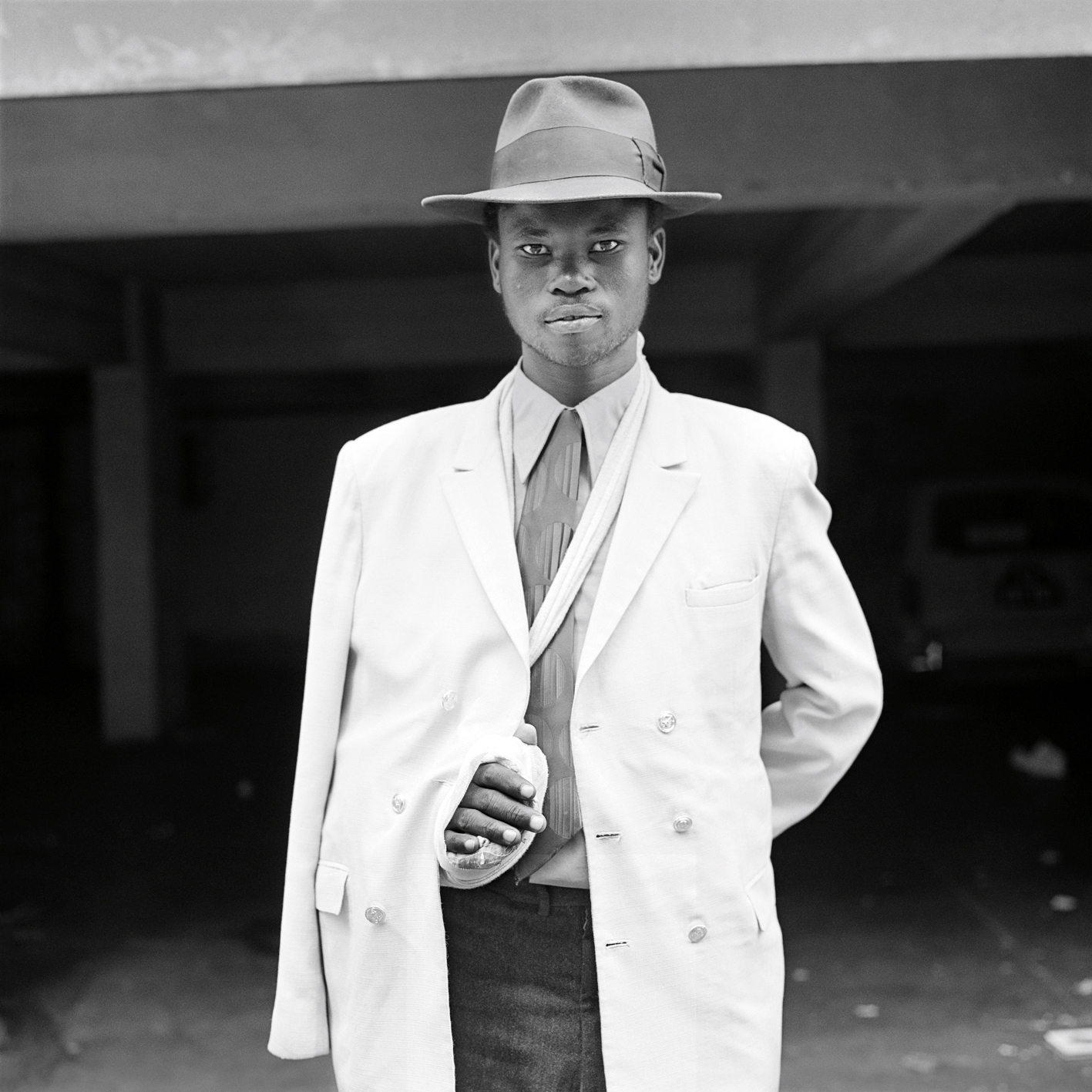

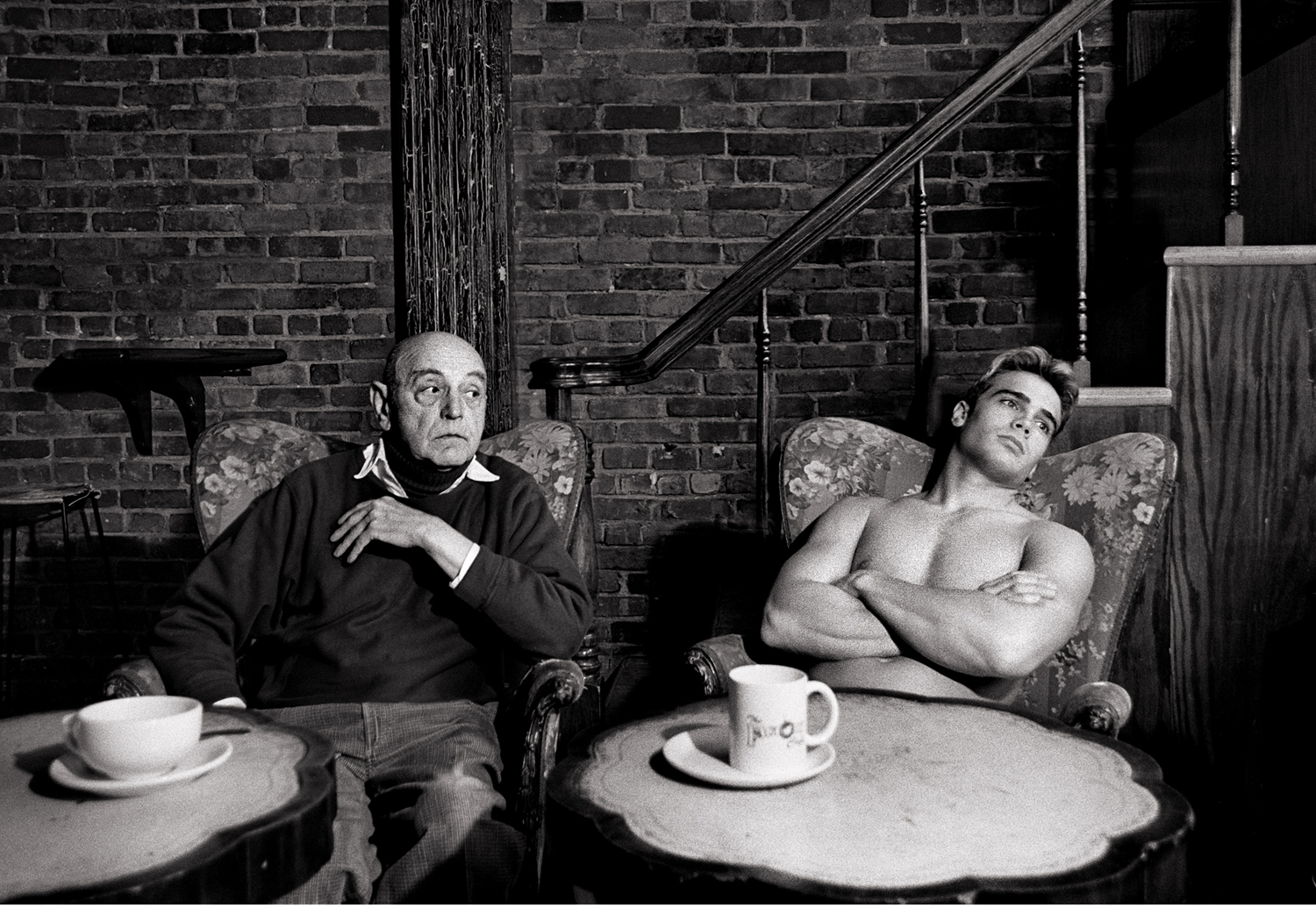

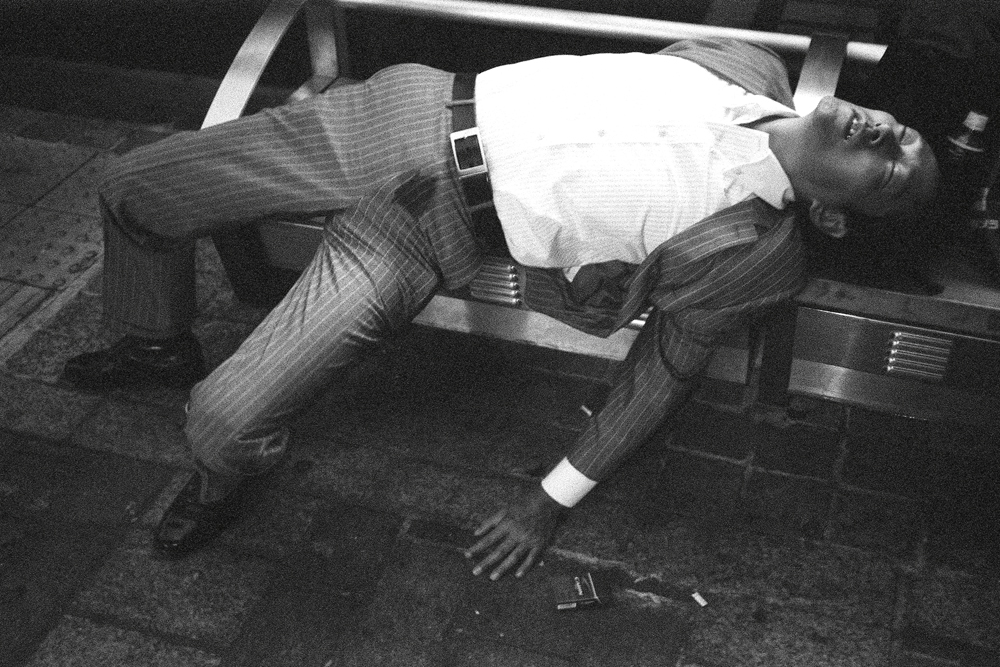

© picture David Goldblatt, Man with an injured arm. Hillbrow, Johannesburg, June, 1972, Black and while photograph on matte paper

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg