Darkness in a blue void.

Front centre a large wooden table.

On the table a disconnected bathtub.

Suspended in midair over the bathtub a MAN.

Greying hair. Earring. Black suit. Leather boots.

MAN levitates parallel to bathtub.

He looks down into the bathtub.

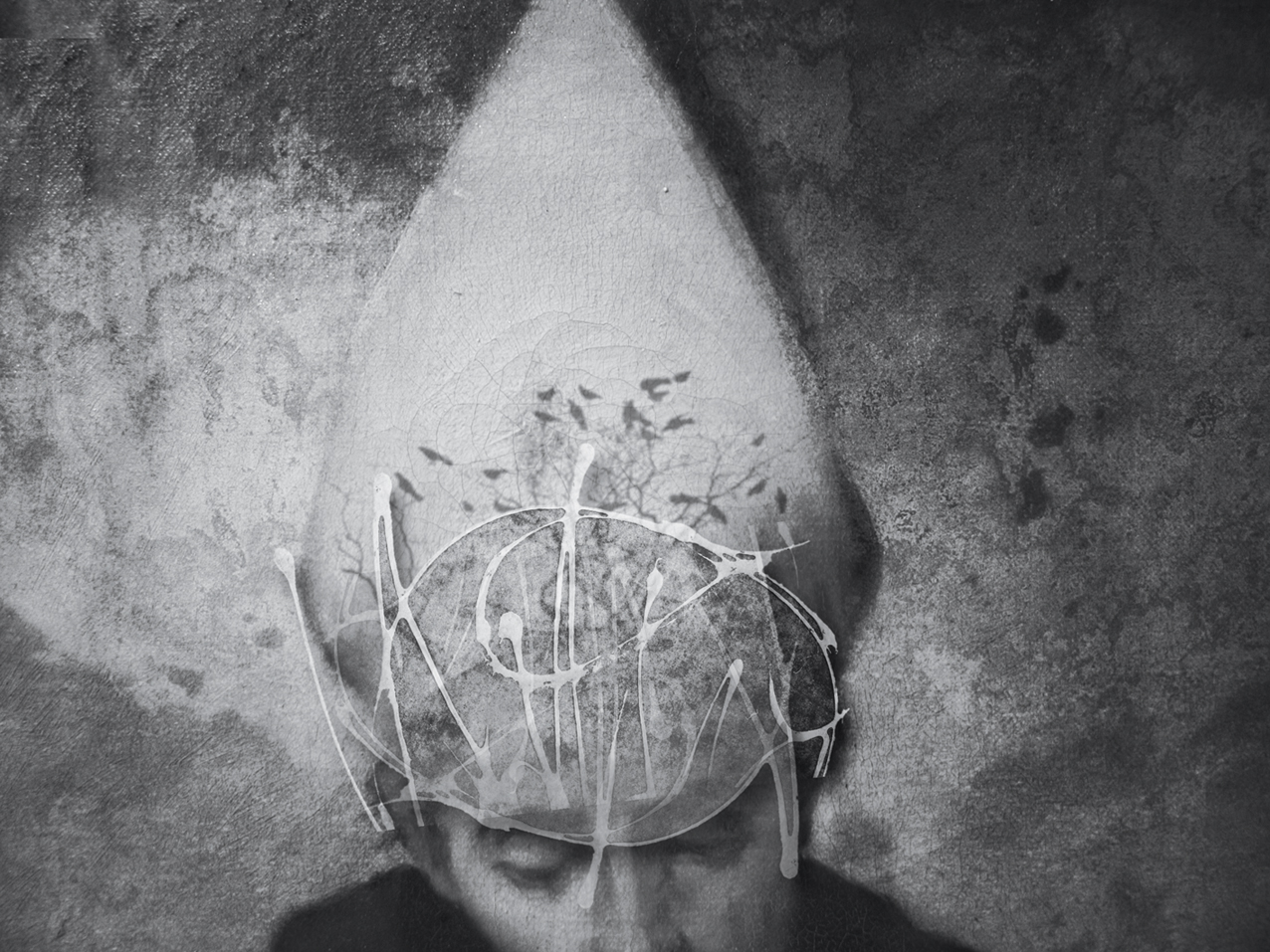

What sounds like stage directions by Beckett is the description of a six-by-eight foot photograph by the artist Jürgen Klauke, “Erstarrtes Ich” (Frozen Self). Klauke’s photography immediately attracts associations unrelated to photography. His photographic oeuvre is a kind of composite artwork and it conveys many of his other art practices in a different form. In that sense, it “translates” his three decades of paintings, drawings, performances, happenings, videos, book publications, and “scribbles” into provocative studies of gender, sexuality, eroticism, and the boundaries of the mind. It also translates Klauke’s aversion to middle-class morality. The artist, presently a professor at the School of Media in Cologne, Germany, admits to growing up “in a bigoted Catholic household in Cologne” and realizing early on in his career that a “social middle class sense of morality has no place in the art world.”

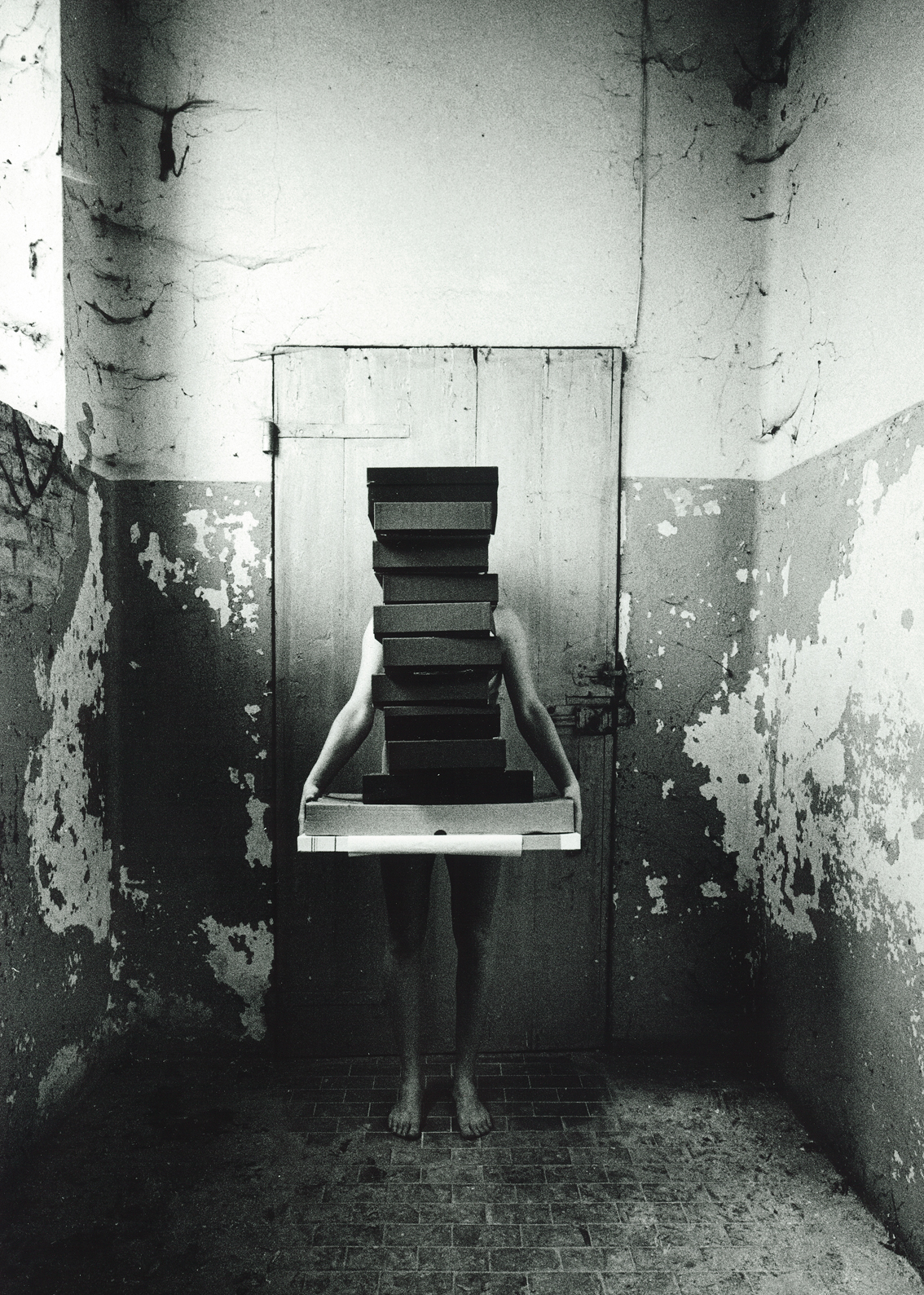

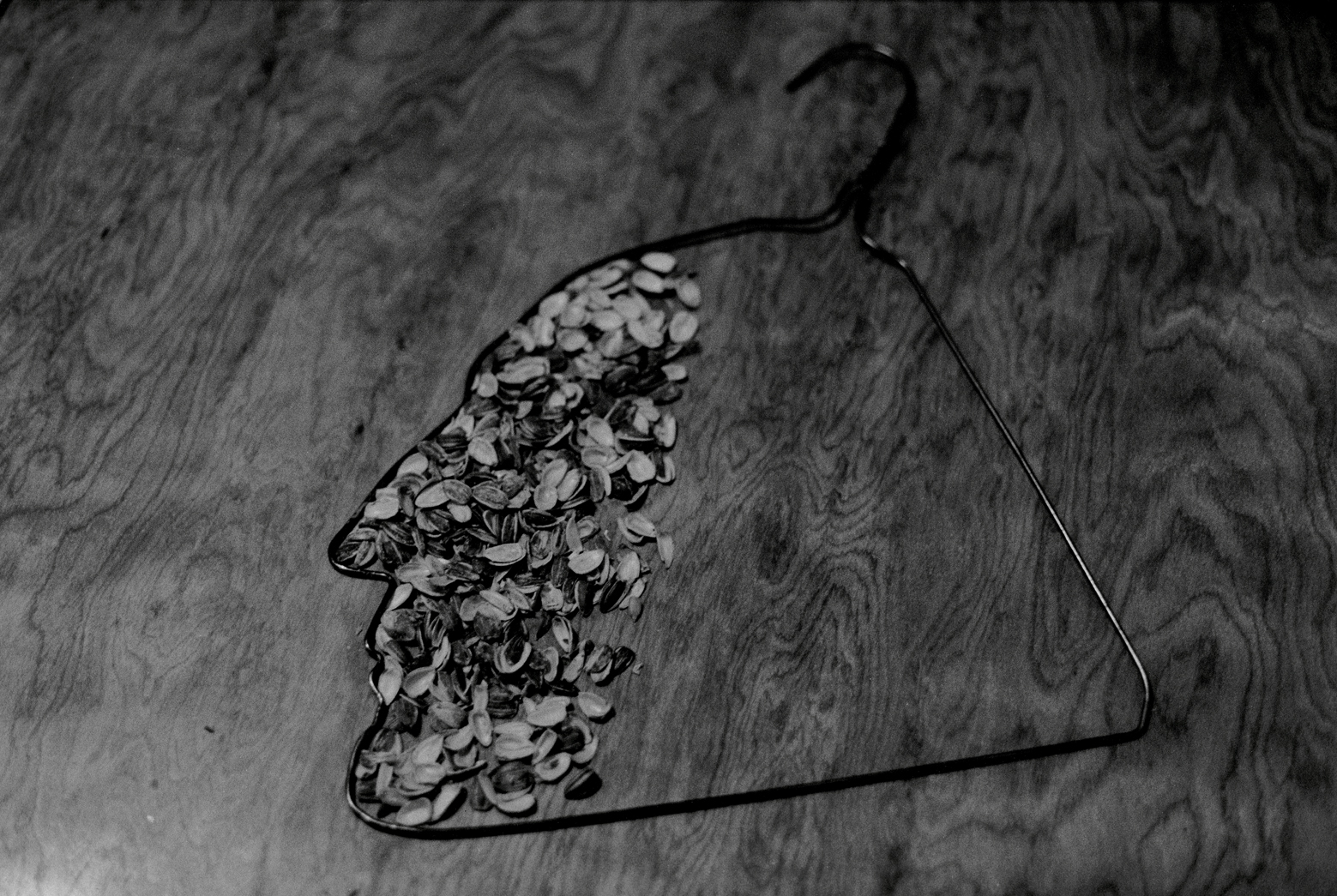

Via Klauke’s command of several media, we enter his photographic works as though entering a theatre of mental images where the plays are rituals with a muted affinity to language, art, philosophy, and underground music. Among the frequently used stage-props we find the table, the chair, the cane, the balloon filled with water, the tower of derbies, and the bucket. The photographed object, the human subject, and the title of the photograph build a unity in these productions. All three serve as indispensable performers.

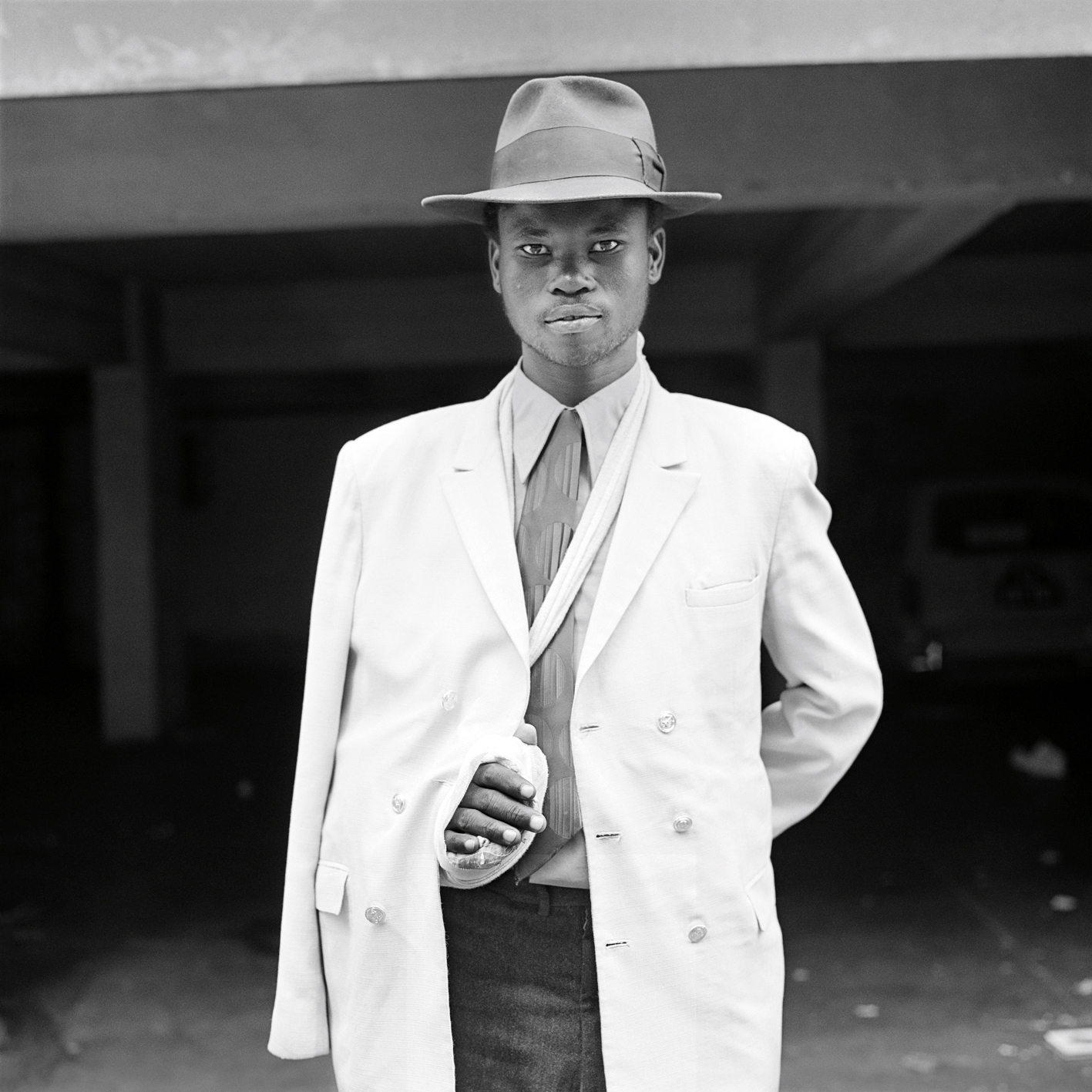

Jürgen Klauke’s photography has already covered a lot of ground: from his black-and-white clown shows of the “Greetings from the Vatican series” – starring the artist as an archbishop wearing a see-through bra and garter belts under his vestments – to his multiple personality self-portraits; from his “self performances” with masks, make-up, the antlers of a stag, transsexual posing, and “red leather” bondage costumes with hints of vintage David Bowie (“Masculin-Feminin” and “Transformer”) to his photographs practically Dogma-like political film sequences; and from his abstract photo-sequences reminiscent of Hans Richter’s surreal film “Dreams Money Can Buy” to his enduring trademark in recent self-portraits – his businessman-magician or man-in-black look.

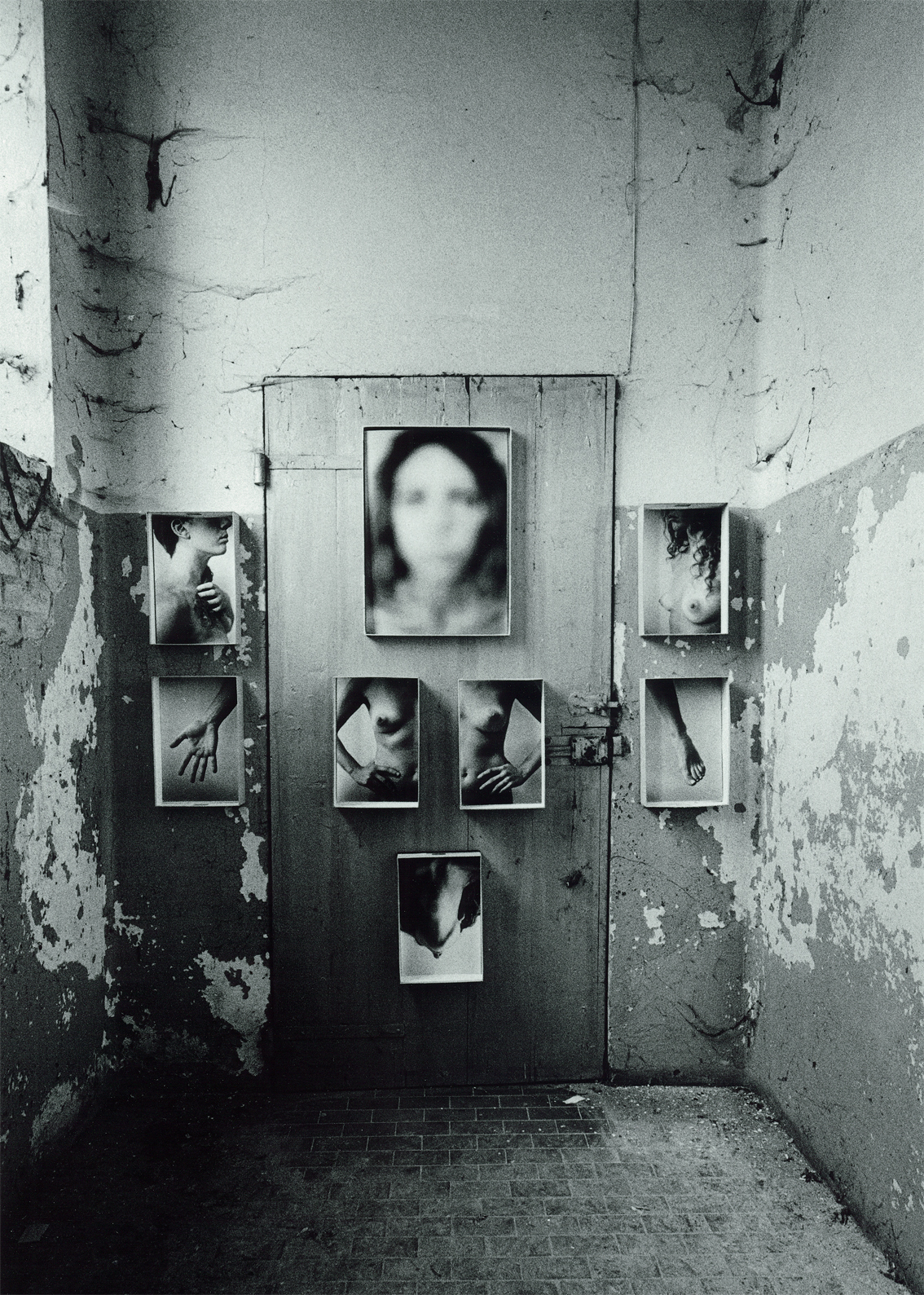

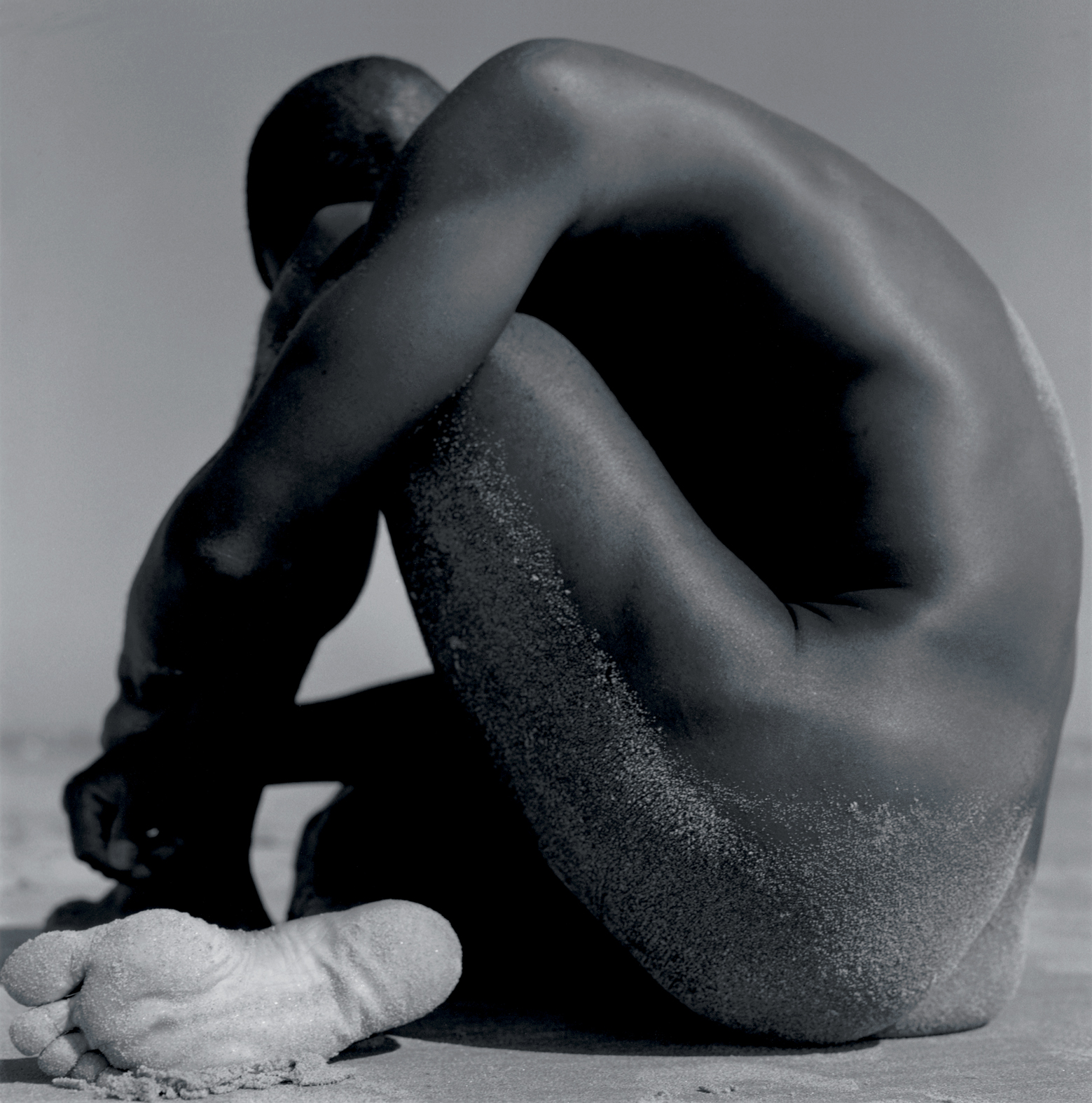

In these works the presence of the human body (often Klauke’s body) consistently points to ways of conceptualizing the body. Some of the photographs suggest “philosophical” mug shots that document how suspects transform, pause, and contemplate, and not merely how they look after the alleged crime of being; some suggest abstract human remnants in a work of “Concrete” photography, and others a human body charged with the kind of sexual longing and sexual ambivalence siphoned from archetypes of Pop and Rock culture.

In Klauke’s later works, however, like in “Frozen Self” and the other “monumental” blue or red-toned images, the human body is reduced to a naked or clothed piece of inventory and becomes more like an “art object” – or more like a living shrine. Among these photographs we also find images where no human subjects at all appear and the object world dominates, or images where the human subject has sombre or hilarious encounters with shelving units, tables, or chairs. In every case, though, the photograph evokes a wrestling match between the human body and “existence” – or as Klauke says: “The grotesque temporality of existence”. Under closer inspection the photographs reveal states of mind caused by questioning the moral and psychological fibre of Western society, which allows them to function at the same time as reflections and attacks on bourgeois longing, living, and loving. They interrupt the accepted patterns used to convey beauty and take special aim at the viewer’s nervous system. Their aesthetic brilliance is simple: we experience visual and conceptual Spartanism as a form of excess, and while the photographs document embodiments of longing, living, and loving, they distance themselves from any “traditional” photographic documentation of such human capacities.

Klauke’s imagery operates strongest at three crossover points: where description becomes invention, where the masculine becomes the feminine, and where photography struggles to remain photography, since his works advocate a distinction between “photography,” used to document the outside world, and “art photography,” Klauke’s preferred photography, used to document an inner expression of freedom. Behind all this stands the unmistakable humour of a sceptical optimist who produces carefully staged “dark comedies” on the banalities of life. This too, somehow refers to the opening association. In Beckett’s “Endgame”, the old woman who lives in the trashcan tells us: “Nothing is funnier than unhappiness”.

In 1994 and 2005, Jürgen Klauke and Cindy Sherman were exhibited together. In 1994, they shared the exhibition spaces of the Goetz Collection in Munich. Apart from being an exciting “two-part” solo, the exhibition was an intriguing comparative study of two photographers with compelling similarities. Both artists are masters of the photographic self-portrait. Both treat life as a theatre, film, or circus; and both investigate the relationship between human beings and photography. But while Sherman ultimately “turns her attention to fashion, food, myths, war, and art history,” Klauke – via “male fantasies” made intoxicatingly narcissistic and voyeuristic in the photo-making process – ultimately concentrates on a mental dialog between the body and the world of objects.

Sherman and Klauke both portray themselves as androgynous creatures in a netherworld between life and art, but one major difference is their unalike inner-calling. As a child of the enlightened 60s, representative of a generation of artists such as Vito Acconci, Duane Micheals, Klaus Rinke, and others who pioneered Body Art, Klauke’s art seems to insist on paying tribute to that other era. Put differently, his art seems more driven than Sherman’s art by the doctrines of an art generation that secured photography’s acceptance as an art form in the first place. Hence the different and not always so different reception of the two artists. A journalist once called Klauke’s art “Un-German” (Sherman’s art is surely “Un-American”), and Meret Oppenheim referred to it as “a little beautiful and a little dirty at the same time”.

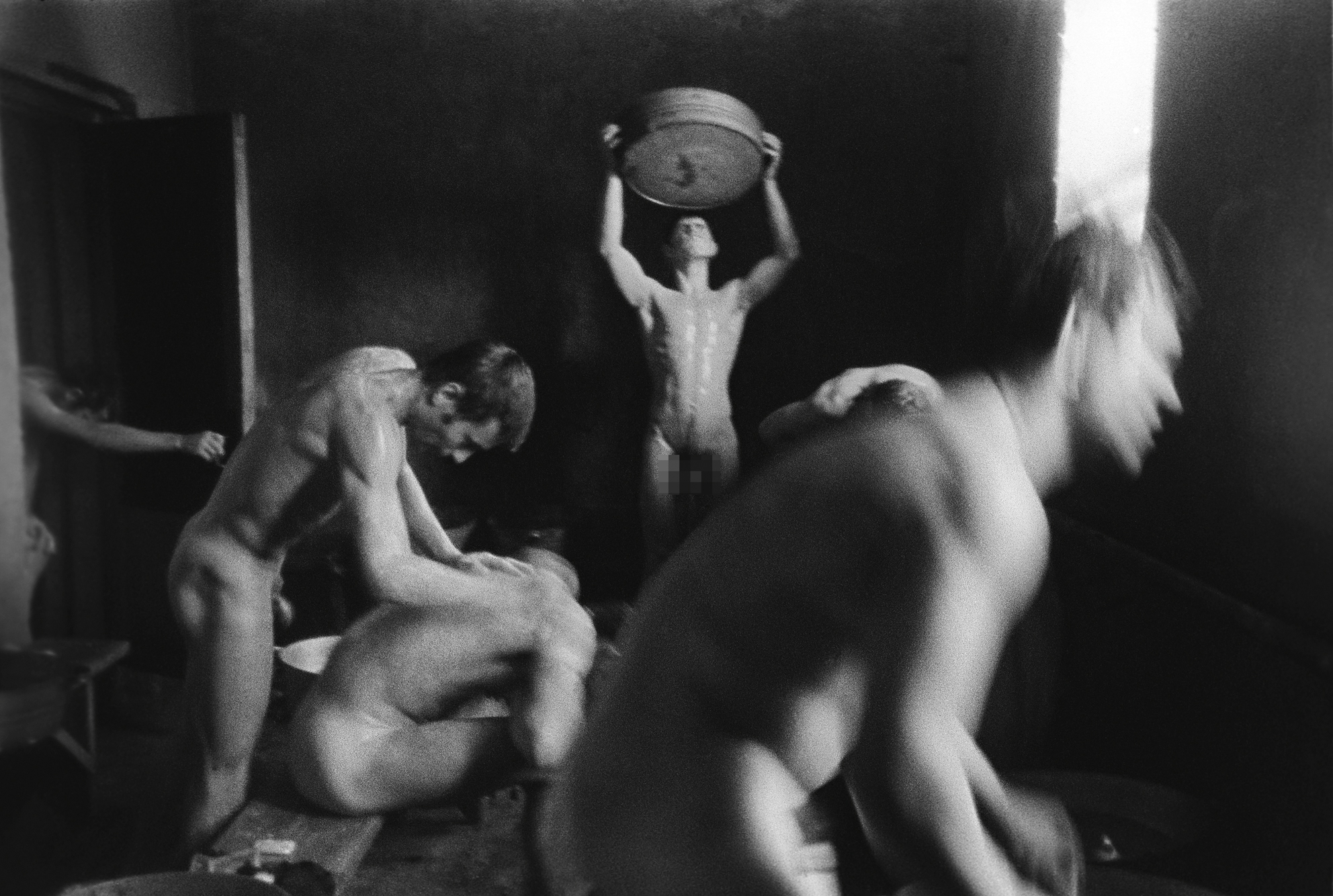

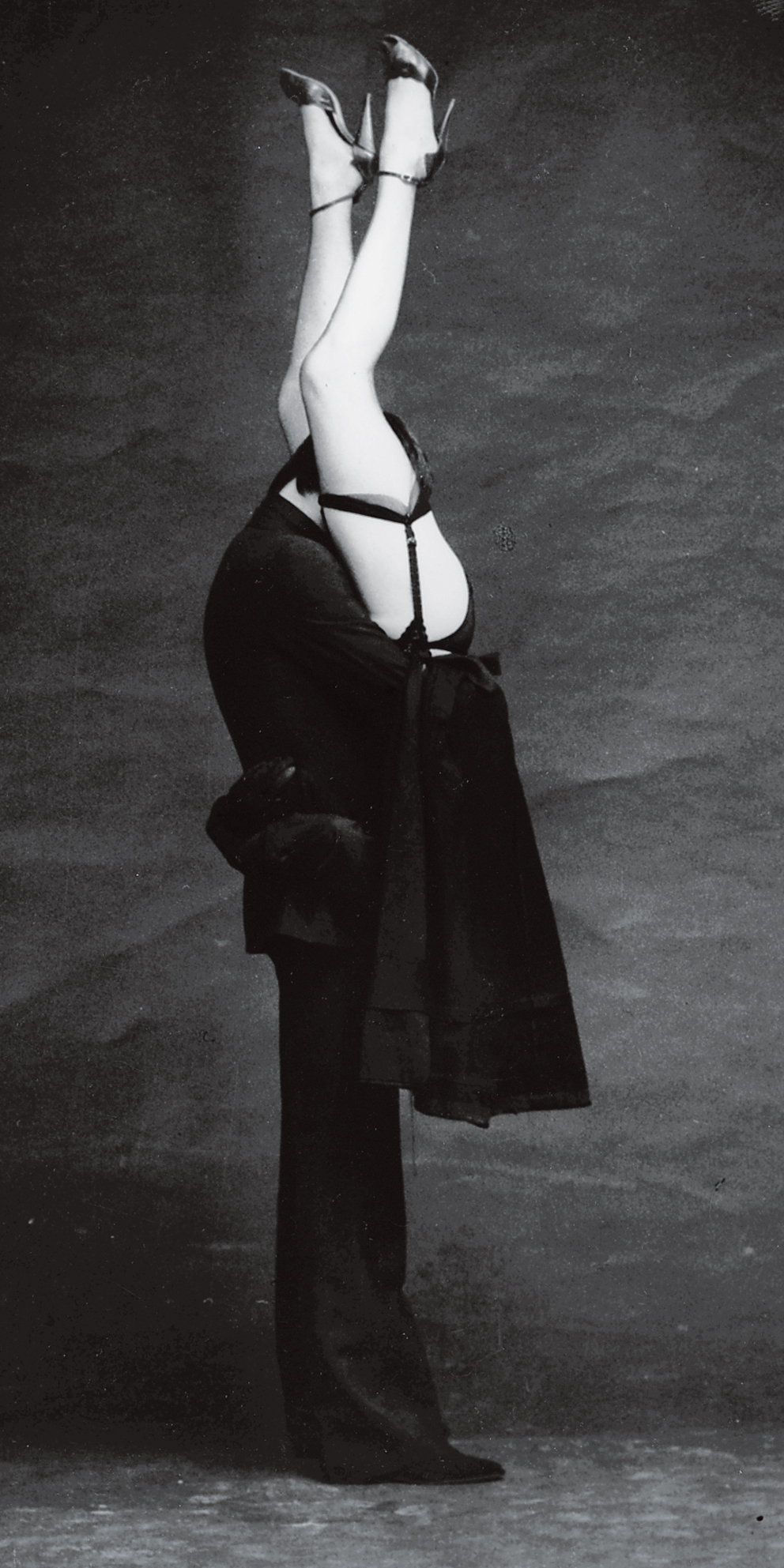

Oppenheim’s reference could probably apply to the photo-sequence “Viva España”. In its individual “stills,” the faces of the two performers (man and woman) remain cloaked by their black garments. HE holds HER elevated in a variety of acrobatic positions, and, while her legs – revealing high-heeled shoes and garter belts – hang over his shoulders or rise up like antennae, project from under his arms or bend in midair at the knees, they perform a “dance” that seems to involve sex in a standing position. In the last still, with the woman upside-down now, they come to rest on a chair, united in a pose resembling the body of an insect. This photographic performance – one of the artist’s earlier demonstrations of how life and art merge – seems dominated by dirty dancing.

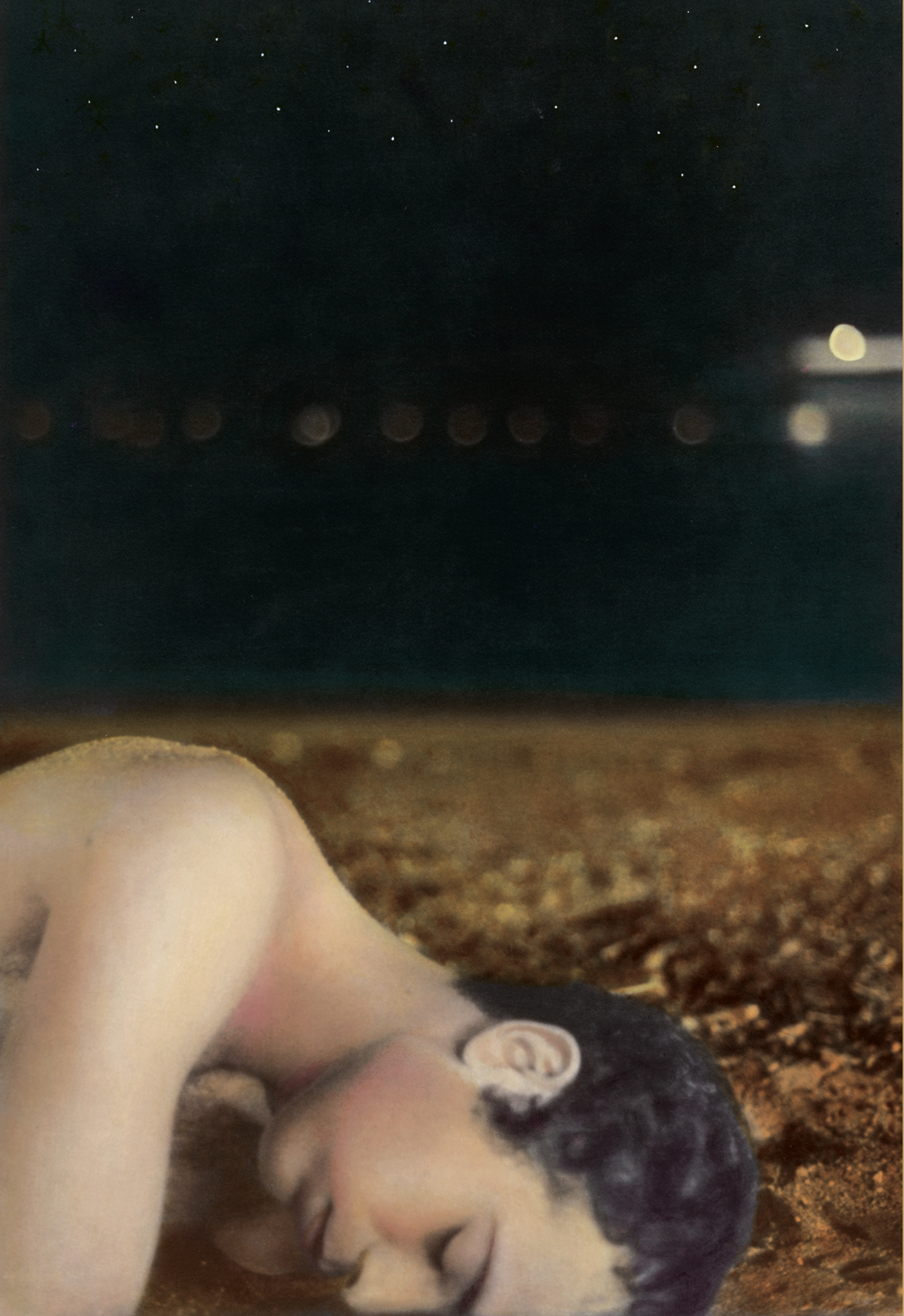

But in Klauke’s recent photographs the mental issues dominate. Patient and at peace with themselves, the artist and his human subjects appear in monumental picture frames, and, with their own bodies, they conduct what appear to be studies on loneliness, gravity, death, and run-of-the-mill boredom. The colour, stillness, and symmetry of these images only seem to have a high-profile portraiture quality. In reality, what passes for a visual aesthetic is actually a mental one, and the compositional simplicity nearly blinds us to the reference being made to a “transfigured soul becoming a transformed soul”. The visual or spiritual fixation of these images refers more so to “states of mind” like desire and hope, and to boredom – a state to which Klauke owes a great deal.

In his photo-series “The Formalizing of Boredom” – completed after “suffering an artistic lull and unbearable sense of repetition in life” – he chose to give a form to what was threatening to undo him then. At the core of this body of works on the complexity and lunacy of boredom – featuring Klauke with a plastic bucket covering his face, the bucket signifying the world “kicking the bucket” – is the realization that boredom is a unique mental state “part motionless, part unfilled periods of time,” and part insidious game played with the senses. It arises from an exaggerated moment of inactivity; it transforms its victim when emotional, social, and psychological factors such as love, work, and belief fail to operate properly. But most importantly, boredom not only tells us something is wrong; it tells us something really exists.

The “visualized” state of boredom in Klauke’s works causes a transformation of the identity that recalls Rimbaud’s famous remark: “Je’est un autre” (I is another). At times it also camouflages the identity of the photograph. Like with the huge blue or red images, and the works compiled in 2000 for the artist’s book, “Trost für Arschlöcher oder Desaströses Ich” (Consolation for Assholes or The Disastrous Self ), what appears to be a denouncement of life or happiness is only Klauke’s photography running its usual course and functioning as both an information carrier and information transformer.

From the late 1990s to the present, Klauke’s monumental blue and red-toned photographs express his artistic concerns on a grander and almost classical scale. In spite of their “empty” appearance, none of his artistic trademarks are missing – whether the poetic reference, the meaning-laden choice of title, and (Rock) musicality in the photograph’s blurred sections, or the “Absurd Theatre” gestures of the human subjects and the staged moments of nudity. Viewed individually or in groups, they create a perfectly balanced Theatre of the Self. They refer as much to sculpture and dance as they do to “art photography,” and their use of “photographed” time, space, and signs illuminates the humane-erotic adventure at the root of Klauke’s works: the journeys forged by thought-provoking mind games that revel in the “condition humaine”.

“Before staging a photograph, a good deal is imagined and figured out in advance,” says Klauke. But this hardly simplifies things. The selection and placement of the used objects are of paramount importance: “The way an object is used decides whether the work speaks of freedom or restraint.” Much of the selection process is handled beforehand in texts and later transposed into images. But, while making the actual photographs, “the objects and the human subjects have to be drastically reduced and yet leave room for sensuality and poetry”. And searching for any supportive visual material along the way only generates the problem with the visible and the invisible: “What I need and prefer are my own images. I need what isn’t there more than I do what is [...] I work my way down through the crust of an idea, bit by bit, mistake by mistake, toward the true sense of an idea.” Which echoes another of Beckett’s ironic sayings: “Try, fail, try again, fail better.”

When an artwork is about life, what could be more difficult than capturing the exact sense? Here Klauke’s philosophical bent comes to his rescue: “I don’t necessarily pursue any greater sense. On the contrary, I formulate the totally senseless, and, in turn, that’s what gives me a sense – for a while”. What helps convey this sense is his carefully contrived system of codes, composed of constellations of objects. For example: Table = World, Bucket = Eliminated World, Table + 3 Hanging Buckets = Stillness, etc…

So it happens that when the curtain rises, that is, when our gaze rises to one of the blue or red-toned photographs, we see what resembles a staged construction on the one hand, and the last traces of a happening or just-documented event on the other. In this setup, the atmospheric density of the blue or red void seems to suggest music. Our eyes can almost “hear” it – a kind of soundtrack in these oddly mythological images intensified by titles like “Annäherungsakrobatik” (The Acrobatics of Coming Closer), “Warteschleife” (Holding Pattern), “Zweisamkeitsimaginierung” (Illusions of Togetherness), “Dritter Wiener Richtung” (The Third Viennese School), “Entrückungserlebnis” (Feeling Enraptured) and “Phantomempfindung” (A Phantom Sensation). Regarding the titles, what the artist does compares to naming the entirety of one poem with the entirety of another. What astounds us the most is the vastness of the photograph’s used and unused space, and watching a framed two-dimensionality masquerade as a three-dimensional performance.

On a visual level, Klauke’s early experiments with X-ray photography also seem present here, at least where “the external appearance of objects and human subjects dissolve, lose a portion of their meaning, become de-individualized, and transform into something else, into something entirely new”. While encountering this “something entirely new” in a piece of straightforward photography like “The Acrobatics of Coming Closer”, we have the impression that we see right through what looks back at us. Yet the surface and content of other images remain as locked away from us as a stranger’s thoughts. And so the MAN who carries out the perplexing experiment with the rectangular shield harpooned with canes wins our attention without us ever learning what it is he discovers right before our eyes. Or we have pictorial variations like the one in “Phantom Sensation”, where sharply focussed or blurred objects – in this case, a stack of derbies – levitate, tumble, and fly out of the frame of their own will.

What these coded mental-scenarios or fragments of dream-happenings would never have us forget is that the artist is aware of the world’s violence and cynicism, and of the mediocrity of life. They want to tell us that his goal is not to create art for art’s sake, with his back turned to the world’s shortcomings. On the contrary, Klauke’s goal is to look directly at life, at the “grotesque temporality of existence,” and to visualize it as best he can from both sides – from the world’s morbid standpoint and from his own memories, sensations, and experiences.

In March 2005, a selection of Jürgen Klauke’s works made an appearance at the DFOTO International Photography Fair in Sans Sebastian, in Northern Spain. And no other word but “appearance” applies. His blue-toned photographs appeared in the exhibition space in the same manner that spirits, angels or visions might appear. From one moment to the next. Maybe there, maybe not. Represented at DFOTO by the Paris-based Gallery Cent 8, Klauke’s photographic “mind games” not only overpowered the space; they seemed to bring all the movement around them to a standstill. It was as though they were repeating the title of the recent publication on Klauke’s complete photographic works, “Absolute Windstille,” which refers to that moment when the wind comes to a halt and imitates the stillness of an object.

TEXT BY KARL EDWARD JOHNSON

©picture Jurgen Klauke